Historic names included on stones for Fonthill, Hillside cemeteries

BY VOICE STAFF

There are now seemingly endless options for what you can have done with your body after death—cryonic freezing, cremation, being blasted into space among them—but in 1802, Isaac Misener just wanted to be buried in dry ground. Misener, who lived in Port Robinson, thought it too wet there, so he asked John Brown to start a graveyard here in Pelham, later to become the Fonthill Cemetery.

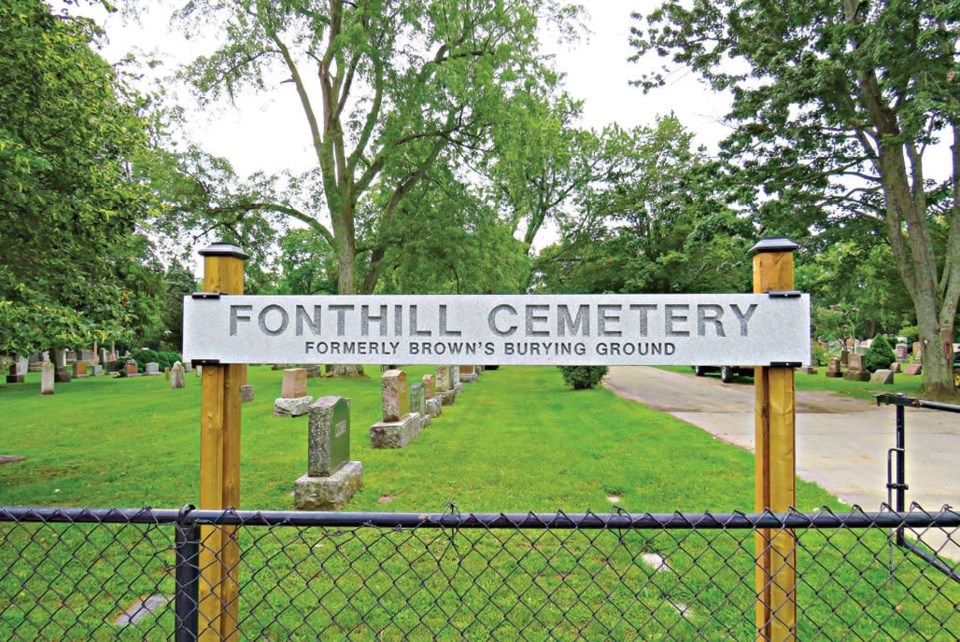

Last week, part of this history was restored to the site: two new signs were installed at the north and east entrances, reading “Fonthill Cemetery” in large lettering, but with “Formerly Brown’s Burying Ground” inscribed underneath.

The graveyard in Ridgeville will also receive a new marker, this one denoting “Hillside Cemetery,” with its former name, “Dawdy Burial Ground,” in smaller lettering underneath.

These changes are largely the result of work by Cindy Fishburn, the Pelham Historical Society’s resident “cemetery expert.” In February of 2016, after hearing that the Town intended to replace the old metal signs, Fishburn petitioned Pelham Town Council to include the former names of both sites. This, she says, is to make it easier for people to locate graves they’re looking for, since many archival records refer to the antiquated names. Fishburn has noticed that “people are now interested in tracing their roots and finding the resting places of their ancestors,” citing the efforts of genealogical societies in arousing public interest.

Fishburn is not the first to seek recognition for the Ridgeville cemetery’s former name.

In 1985, a descendent of the Dawdy family, Tony Whelan, argued to council that Hillside Cemetery should have been returned to its original name. Whelan’s great-great-great-great grandfather, Jeremiah Dawdy, first settled the land in 1806, and in 1815 began turning part of it into a burial ground. Though in 1933 the iron arch that reads “Hillside Cemetery” was erected, Whelan claimed that the land had never been legally sold to the town. In 1987, council voted unanimously to end discussion and retain the name “Hillside.”

Whelan was not pleased. He told the St. Catharines Standard—in a story describing him as “noticeably shaken” by the decision—that “Revenge is in the air. I’m not giving up…They haven’t heard the last of me.”

In justifying the rejection of Whelan’s proposal, alderman Lloyd Tunnacliffe said that it was inappropriate to name the cemetery Dawdy, since some of its land was at times owned by the Becketts and other local families. Whelan died last year, though Carol Dawdy Wright, who had helped Whelan in his efforts, called Cindy Fishburn to thank her for her efforts.

Back in Fonthill, Brown’s Burying Ground has had a less controversial history. In 1873, John Brown III (the founder’s grandson) gave ownership of the land to the township, and in the early 20th century it became known as the Fonthill Cemetery.

For many years, maintenance of the grounds was left to the relatives of those buried, with the result that the plots whose families had moved away or died out soon became overgrown.

In the early 1900s, a Dr. Harry Emmett took it upon itself to organize the tidying of the grounds, and in 1923, the town took complete control. The mausoleum, built in 1926, has no remaining space, while less than three quarters of an acre is still open for new graves.

Hillside and Fonthill Cemeteries are the only ones operated by the town, though there are several other graveyards in Pelham, the largest of which is on the corner of Cream and Metler streets in North Pelham. This cemetery has always been public, and has never had any connection to the Presbyterian church across the street. The graveyard at the Effingham-Welland intersection, and the Hansler burial ground near Bissell’s, however, were always explicitly Quaker sites. Quakerism, a sect of protestantism known for its doctrine of pacifism, tee-totalling, and participation in the anti-slavery movement, experienced a fracturing in the 1820s. Here in Pelham, those who adhered to Elias Hicks’ teachings left the orthodox Quakers and began their own cemetery on Haist Street, now across from Harold Black Park.

The histories of graveyards provide valuable insight into the history of Pelham—and so too do individual graves provide insight into the history of families. If the internet is any indication, Fishburn is right about renewed interest in genealogy. There are myriad websites on which such information can be found, most notably ancestry.ca.

Even more recently, personal DNA testing has become affordable, with sites such as “23andme” offering home kits for a few hundred dollars or less. These kits are simple: using a swab provided, you send a saliva sample into a lab, where your DNA is scanned and analyzed. The service subsequently sends out a private report, which typically includes information on linguistic history, geographical location, Neanderthal lineage, and genetic diseases. The service compares your DNA with the samples in its database, which has some one million entrants, and as a result can identify family linkages around the world—or down the street.

In 2012, human remains were found beneath a parking lot in Leicester, England. Using DNA testing, including samples from Canadian Michael Ibsen, the body was determined to be King Richard III. Richard died during a battle against the Tudors in 1485, and while Ibsen had always heard rumours of his heritage, it wasn’t until his DNA was tested that he could definitely say that he is a 17th generation nephew of the king.