Surviving a cardiovascular episode

BY DON RICKERS Special to the VOICE

It was a bright January afternoon, a Saturday, over a year ago. I was standing at the kitchen sink, drying dishes and cutlery from lunch. My mind wandered to the hockey game from the previous day, and the impending skate on Monday.

Twice-a-week old-timers recreational hockey was an enjoyable part of my retirement regimen. At 60 years of age, I was in pretty decent shape (despite carrying a few extra pounds) thanks to rowing workouts and regattas April through October, skiing in the winter, regular bouts of weight training, and copious hours of outdoor chores around the house.

I felt, to quote notorious Watergate burglar and political commentator G. Gordon Liddy, “Virile, vigorous, and potent…just ask Mrs. Liddy.”

As I critiqued my on-ice performance, convinced that one of those $300 carbon-composite hockey sticks would add a few miles-per-hour to my wrist shot, it happened. I felt a dense, grey wave wash over me. My vision dulled; my hearing faded. It’s as if my head was immersed in a tub of Jello. I sensed a pop in the back of my skull, and things got fuzzy fast.

I managed to place the plate and dish towel on the counter before they fell from my hand. The room was spinning faster than a politician’s press release, and my balance became precarious.

“Something’s wrong with me," I muttered to my wife, Anne. She turned to see me stagger across the kitchen like a drunken sailor and plop myself on a nearby stool. Just to ensure she knew I wasn’t kidding around, I proceeded to upchuck the pasta carbonara she had served for lunch.

“Must be food poisoning,” I groaned to Anne, failing to recall that she had eaten the same meal. Besides, she was pretty much a gourmet cook; sub-par ingredients would never pass muster. She charitably let the insult pass.

Our Cocker Spaniel, Sam, stared at me with a quizzical expression. He had shared our meal, and his pasta had tasted just fine, thank you very much. In fact, Sam had gone back for seconds.

I made my way haltingly to the living room, bouncing off the occasional wall en route. I collapsed on the couch, and attempted to comprehend my predicament.

Heart attack? No way. I had never had chest pain in my life. No distress during vigorous exercise. I had always sweated like a race horse in heat, but that was normal for me. My heart was A-1, for sure.

Stroke? Nope.

I couldn’t recall ever suffering a headache. Ever. I had no paralysis or weakness in my limbs, no speech impairment, no mental fog. So definitely not a stroke.

Gotta be food poisoning. Right.

Once I purge the offending toxin churning away in my stomach, it will be back to blue skies and rainbows.

I felt drunk, like I had gone a dozen rounds with Jim Beam, Jack Daniels, and Jose Cuervo. (Three against one; not a fair fight.)

Anne insisted I go to the hospital. Ever the stubborn fool, I declined. This dizziness will pass, and my balance will return after a short nap. Plus we’re going out for dinner with friends tonight, remember?

The phone rang a few minutes later. It was my friend Dave. Anne had called him to try to convince me to seek medical attention. Dave admonished me for my delaying tactic, and instructed me see a doctor immediately. You worry too much, I told him. No headache, no chest pain, just dizziness and nausea. It’s a virus or some polysyllabic bacterial infection. I’ll be back in the pink before you know it.

We had to cancel our supper plans on account of my malady, but I was sure a good night’s sleep was all I needed.

By 4 AM I was still wobbly on my pegs, and the dizziness had not abated. Okay. Mea culpa. Maybe I should pop in to the hospital. They might be able to prescribe some pills for whatever is ailing me. But if the waiting room is full, I’m not sticking around all day.

I was not delayed long in the St. Catharines emergency waiting room, probably because upon arrival I projectile vomited all over the floor. That surely impressed the hell out of them. Let’s move this guy to the head of the line, the nurse on duty decided.

After a brief chat with a very pleasant but rather frenetic emergency room doctor, I was piled onto a gurney and wheeled over to the radiology department for a CT scan. They blasted me with x-rays to create cross-sectional, three-dimensional images, kind of a like digital slicing, no Ginsu knife needed.

The animated ER doctor (whose coffee breath explained his reservoir of energy) proceeded to give me the news: congratulations, you have just delivered a fully-blocked vertebral artery. Also known as an ischemic stroke. That’s the first time he had used the word. Stroke. A chill ran down my spine.

Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability in Canada, and the third leading cause of death. Some 14,000 of us strokers meet the Grim Reaper annually, with 50,000 suffering new strokes (one every ten minutes) per year. A quarter of stroke victims in this country are under the age of 65, with risk rising dramatically after age 55.

There are four arteries which feed your brain: two in the back of the neck (vertebral) and two in the front (carotid).

My right vertebral was fully choked; my right carotid had a 60% blockage. Had I been more sensible and called 911 on the Saturday afternoon, doctors might have been able to give me a clot-bluster to open the blocked artery, which had starved my brain cells responsible for gross motor co-ordination. Hence my balance issues.

But the drug needs to be administered within a few hours to be effective. Hopefully the millions of other untasked brain cells hanging out in my cranium would get the call to shovel their dead buddies into the neural network dumpster and take their place in equilibrium central.

The doctor assured me that I had dodged a bullet (well, actually it just grazed me) and should make a full recovery. But just to be on the safe side, they were going to transfer me to the Niagara Region’s stroke centre at the Niagara Falls GeneraI.

Upon my arrival at the Niagara Falls site, I underwent additional CT scans, and met with more doctors. They did not paint the rosy picture that Dr. Espresso in St. Catharines had.

A dour older MD opined that I would never play hockey or ski again, fearing my balance might be impaired permanently. Another doctor chastised me quite sternly for being a regular cigar smoker. (Jeez, a guy needs a hobby…what’s wrong with a daily Macanudo?) She lectured that even though one does not generally inhale cigar smoke into the lungs, nicotine and other toxic chemicals quickly penetrate soft tissue and enter the bloodstream.

How long had my blood pressure been so high, they inquired? A while, I responded. Quite a while, actually. Okay, maybe throughout the last decade. I had a home unit and tested my blood pressure on occasion, and knew that I was well north of 120 over 80. I concluded that I was in the “pre-hypertensive” category, and would be fine if I shed a few pounds, cut back on my salt intake, moderated my fondness for cigars and cabernet, ramped up my exercise program, and worried less about stressors at work.

No doubt some of my blood pressure issues were hereditary. But my parents and grandparents had all lived into their late 80s and early 90s. No early heart attacks or strokes. My dad used to say that he gave heart attacks, he didn’t get them.

I realized I was going to be here for a while, and grudgingly accepted my fate. The orderly wheeled me into the residential room which was to be my home for the next five days.

I thought my insurance plan upgraded me to single accommodation, but here I was, staring across at my new roomie: a lean, 80-something fellow I’ll call Lars, who had suffered a stroke much more debilitating than my own. His doting wife was pleasant and considerate of my wish for privacy: Lars, not so much.

He had a rather annoying quirk. As soon as his wife departed, he called out in a raspy baritone every 30 seconds or so, “Darling? Coffeee!” This went on for hours. I pleaded with the nurse, “In the name of God, bring this man a steaming latte!” I texted my wife to inform her that I planned to crawl out of bed around midnight and smother Lars with his own pillow. Justifiable homicide, to be sure.

Mercifully, the nurses moved Lars across the hall the next day. His new roommate was apparently incapable of speech, but I could hear him in the darkness, hammering on the nightstand with his fist in submission, as Lars continued his evening soliloquy.

I attended a rehabilitation session with a wheeled walker the next day, and progressed quickly to a cane. My balance improved daily, and soon I was walking somewhat haltingly without any aid.

The doctors gave me the standard meds: low-dose aspirin to thin my blood, Coversyl (an ACE inhibitor generically called Perindopril) to make my arteries more pliable and bring down my blood pressure, and the statin Lipitor (which is prescribed to control cholesterol). My cholesterol levels were actually within the normal range, although my triglycerides (fat in the blood) were marginally elevated.

Subsequent CT scans detected a cardiac anomaly called a PFO, or patent foramen ovale, which is a small flap-like opening in the wall between the right and left upper chambers of the heart (atria). It normally closes during infancy. PFOs occur in about 25 percent of the population, but most people with the condition never know they have it.

The danger is that blood clots can travel from any part of the body along the cardiovascular highway and through the PFO and get to the brain, causing a stroke. Kind of like a drive-by shooting.

Moving forward, I gobble my pills dutifully like an obedient soldier. I developed tinnitus (ringing in the ears) and am not sure whether it was a result of the stroke or the medication. It’s a bloody nuisance. But my balance has been restored, and I’m back playing hockey, and skiing, and pretty much doing most of what I enjoyed pre-stroke.

As to what exactly caused the stroke, the doctors all shrugged.

The PFO? “Maybe.”

Too many Dominican robustos? “Certainly didn’t help.”

My weekly pilgrimage to Harvey’s for an angus burger and onion rings? “Should go easy on those.”

Too much booze? “Hey, it’s five o’clock somewhere, twice a day.”

Workplace stress? “You’re probably not paranoid, chances are they really are out to get you.”

Bad genetics? “Sure, blame the family tree you fell out of.”

So what have I learned from this experience? What modifications will I make in my life to delay shuffling off this mortal coil?

It’s easy to play Monday-morning quarterback, and profess with evangelical fervor that I am steering clear of fast food, potent potables, the evil tobacco, and other vices.

Truth be told, I now make less-frequent appearances at the Harvey’s drive-through window. And yes, I gave away two humidors filled with my favorite cigars. I’m trying, dammit. I’m making an effort.

But once you hit your sixties, you don’t want to give up that last slice of strawberry-rhubarb pie. Double espresso? Absolutely. Another Chivas, sir? Make it a small one. All things in moderation and try to leave a good-looking corpse, that’s my credo.

I like to think I have become more appreciative of the truly important people and events in my life. I worry less about the things I can’t control, and don’t dwell on missteps of the past. I take more time to enjoy a crimson sunset, and my granddaughter’s smile.

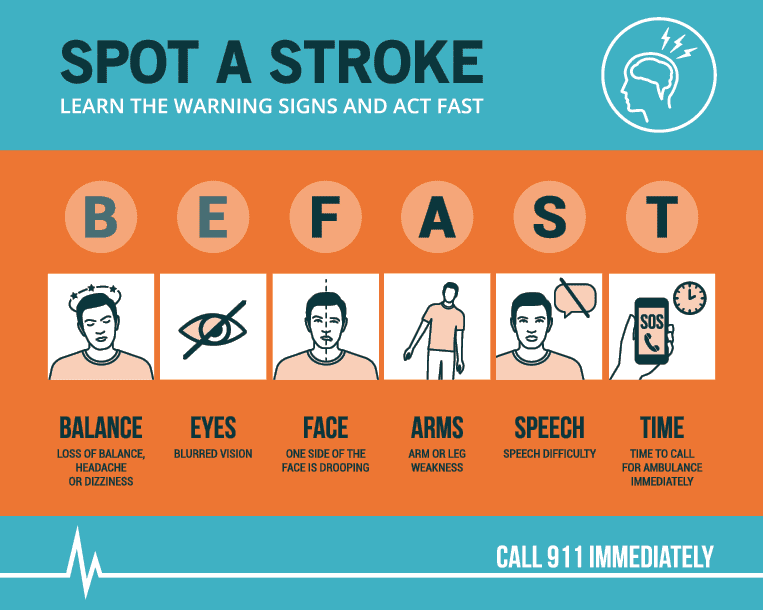

One piece of advice I can offer…and you can take this to the bank. Should any stroke-like symptoms befall you, don’t flutter around like I did. Call 9-1-1 and let the paramedics whisk you to the hospital pronto.

That way, you bypass the waiting room, and go face-to-face with a doctor. Hopefully you’ll get a shot of that medicinal Drano to blast through the arterial blockage, blood flow will be restored, and you’ll be back on the street in no time. ◆