BY GLORIA J. KATCH Special to the VOICE

It was a quiet Sunday on June 3 in the pristine villages of Guatemala. Not unlike other Sundays, people gathered to sing religious praises, or strolled through the town visiting friends and neighbors. No one knew that within a few hours, a sudden volcanic eruption from a nearby mountain would spew ash 33,000 feet into the air as molten lava and fiery gases cascaded over the hillside and villages, melting and destroying everything in its wake. There was no time to evacuate.

By the next day, news reports indicated 192 missing and at least 69 people dead from the villages of El Rodeo and San Miguel Lost Lotes. The nearby towns were covered in a deathly gray hue from this disasterous volcanic purge. Thousands of people were moved to temporary shelters.

“The Fuego, meaning the fire,” catastrophe just added to the already bleak conditions of this area, said Ben Obdeyn, Director of Wells of Hope.

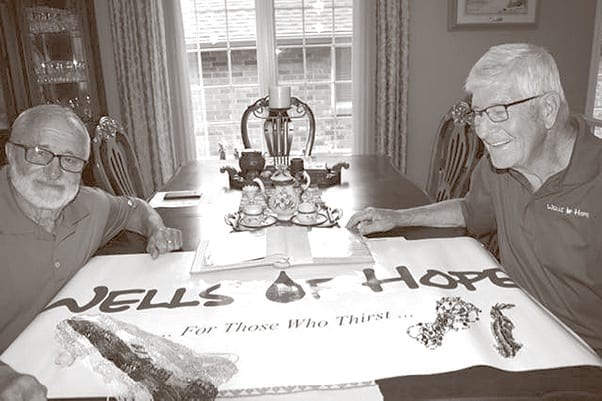

Through this non-profit, multi-denominational organization, Obdeyn has visited and set-up camp in Guatelmala 31 times. He nods to his “partner in crime,” Frank Memme, also a builder and dedicated member of this organization that drills wells, builds schools, and bridges, provides dental health, and contributes to the economic prosperity of Guatemalan’s indigenous community.

Obdeyn got involved with Wells of Hope when he met its founder, Ted van der Zalm, many years ago.

“We’re both Dutch,” he said, laughing.

Van der Zalm was awarded the Canada Governor General’s award in 2016 for his commitment and compassion to some 50,000 people in this Central American country, where so many children die from diseases caused by contaminated water.

Van der Zalm started digging wells in Guatemala in 2004, and was digging wells in Tanzania prior to that. To date, the Wells of Hope have served 65,000 people with clean drinking water.

Van der Zalm started digging wells in Guatemala in 2004, and was digging wells in Tanzania prior to that. To date, the Wells of Hope have served 65,000 people with clean drinking water.

Currently, the organization has fundraised enough to build 20 wells and 24 new schools.

“We try to build two wells and two schools each year,” van der Zalm said, adding that one well costs roughly $150,000 to build, and a school costs $30,000.

Since many of the villages are in mountainous regions, high above sea level, the wells have to be dug hundreds of feet into the ground. Wells of Hope also supplies the electric pumps and generator, as well as the cables and casings. The villagers assist by digging trenches to individual houses.

Fundraising also pays for all the materials for developing the schools, and it pays the masons and roofers to complete the tasks in these skilled trades. The money that Wells of Hope fundraises provides economic income to the communities. The schools are often painted by different volunteers groups from various parts of Canada, which travel to Guatemala for the cultural experience and to collaborate on projects. “We see improvement to the area because of us,” said Obdeyn. Once schools are built, the Guatemalan government hires teachers.

Memme and Obdeyn both believe that assisting the communities is only possible after consulting with them.

“You can’t force your white people’s culture on them,” he said.

One of their members, Peter Mernagh, speaks Spanish and interacts with Guatemalan education officials to help provide books and educational materials.

Memme said women who have been abandoned by their husbands and left to care for their children often approach the organization’s volunteers for help.

“The women are the mules of society,” he said. They believe the education and assistance helps empower women to lead better lives.

This part of the world is also susceptible to drug problems, because of the poverty, and the ability to grow many different drugs, particularly opium for heroine and morphine use.

There are 12 or 13 tribes in the area that don’t always get along, added Obdeyn. Memme also acknowledged there are sporadic skirmishes and fighting, but said, “It’s like any other country.”

Considering all the detrimental factors, there is always a constant need, noted Obdeyn. The Niagara-based committee doesn’t set any specific annual monetary goal for this reason.

“We just raise as much as we can,” he said.

The people in these Regions live off the land, and what little crops they have—staple crops like corn and coffee —barely help them get by. Even the weather can be harsh and extreme, causing drought and flooding.

“It’s a tough, tough existence.”

Despite all the problems, Obdeyn desribes the people as “very religious,” with a sense of festivity. Families congregate often, and enjoy singing, and most of all, each other.

Wells of Hope also collects food, gently used blankets, clothing (particularly children’s clothing), shoes, and housewares, like pots and pans. They also need work clothes and boots, as well as construction tools like shovels, pick axes, electric drills and circular saws. Unfortunately, Obdeyn hasn’t been able to attract a hardware store or similar sponsor that can provide these items. While, Obdeyn is grateful for the donations, the tools need to be operable and in good shape.

This year, donations may be made at St. Alexander Church in Fonthill, and at St. Kevin’s Church in Welland.

Work-related items such as clothes, boots, ands tools may be donated to Obdeyn at (905) 892-4721.

Those who want to make monetary contributions online can visit Wells of Hope.com. Approximately 89 per cent of the money raised goes to Guatelmala, while 11 percent is spent on administration, explained Obdeyn.

When asked how Memme and Obdeyn stay so committed, they both seem to empathize with the hardship and poverty suffered. Memme said he came to Canada after Europe was destroyed by World War II, and he struggled as an Italian immigrant.

Obdeyn sees the difference that Wells of Hope makes, when one of their trucks bringing supplies and goods arrives. After a few minutes, a few people will appear. Then a few more. Within a few minutes, an entire village is lined up watching and waiting for help to materialize.