A childhood home will never be the same

BY JOHN CHICK Special to the VOICE

In my experience, three cities in the world have distinctive smells that permeate. In Vegas, it’s air conditioning, perfume and cigarettes. In New York, it’s peppers, onions, car exhaust and urine. And in Hong Kong, it's the heat. The humidity punches you in the face, overwhelming your olfactory senses with traces of Chinese cooking and rotting tropical vegetation. For an idea of how humid it gets in Southeast Asia between March and November, start with how hot it was on Summerfest Saturday last month, then multiply by ten.

This is far from a complaint.

You haven’t lived until you get in a 6 AM run on Victoria Peak to beat the 35-degree mark, and then spend the rest of the day drinking San Miguel beer on the blast furnace streets, feeling the periodic surge of air conditioning jetting out the wide open doors of a Zara or Louis Vuitton store.

You haven’t lived until you get in a 6 AM run on Victoria Peak to beat the 35-degree mark, and then spend the rest of the day drinking San Miguel beer on the blast furnace streets, feeling the periodic surge of air conditioning jetting out the wide open doors of a Zara or Louis Vuitton store.

I love Hong Kong. Yet, my childhood there (my dad worked at the Canadian Consulate) of guava juice, fried rice, swimming lessons—and the two trips I’ve taken back over the past seven years—were sort of byproducts of its unique history.

Imagine leasing some land in 1897 for 100 years. At the time, nobody thinks about the end of the lease, because quite frankly, nobody that’s around then will be alive when it expires.

During this hundred years, the leased land rapidly grows from an obscure fishing and farming village into a superpower of global commerce. At the same time, the much larger landlord also grows —albeit more slowly— from a collection of obscure fishing and farming villages into a superpower of global commerce.

As a result, 13 years before the lease expires, negotiations begin. The landlord flexes its growing muscles, while the declining empire that is the lease-holder retreats. A lease extension is not considered. Instead, not unlike a Hyundai Sonata with 20,000 kilometers on it, at the end of the contract, the land is ultimately returned to its original owner.

This is the story of Hong Kong in a nutshell. But when Britain handed back the 1,100 sq. km. territory and the fate of its 6.5 million residents to China 22 years ago, the two sides negotiated caveats. Mainly, that Hong Kong would keep its democratic freedoms, separate currency, free press, and British-based judicial system under a “one country-two systems” pact for 50 years, until 2047.

This is the story of Hong Kong in a nutshell. But when Britain handed back the 1,100 sq. km. territory and the fate of its 6.5 million residents to China 22 years ago, the two sides negotiated caveats. Mainly, that Hong Kong would keep its democratic freedoms, separate currency, free press, and British-based judicial system under a “one country-two systems” pact for 50 years, until 2047.

On the surface it appears to work. Unlike China, you don’t need a visa to fly into Hong Kong. When you turn on your phone in the airport after buying a SIM card at 7-Eleven, all of your apps aren’t blocked, as they are in China. And at last check, you don’t really run the risk of disappearing into a prison system in Hong Kong —even if some of the current pro-democracy protesters may be seriously challenging this.

Yet the protests, dissent and turmoil of the last two months are being fed by something deeper. Sure, Hong Kong has lived under the fear of China’s iron fist since the aforementioned handover negotiations in 1984. Almost immediately from that point, native Hong Kongers began fleeing the territory. In time, a large number of my elementary school classmates from the late ‘80s relocated to Canada, the U.S., Britain, and Australia.

Many stayed put, though, because in addition to the fact that it’s their home, life in Hong Kong is pretty good if you can afford it. It was always expensive to live there, but this reality has been on steroids for the last two decades. Housing in Asia tends to be smaller than what we’re accustomed to in North America, and in Hong Kong’s case is mostly limited to towering apartment buildings, given its overall lack of space between snake-riddled mountains and the South China Sea.

A unit like the 2,000 sq.ft. apartment I spent a portion of my childhood in now retails today in the neighbourhood of $6 million dollars (we didn’t own it, the Canadian government did). Rents for infinitely tinier, one-bedroom units (250 sq.ft. anyone?) start at around $2,500 a month. While much of this was originally driven by Hong Kong’s status as a financial centre, in recent years real estate speculators from mainland China have helped push prices up astronomically, as they have tended to do in other major cities—looking at you Vancouver, and to a lesser extent Toronto.

In other words, many of the same millennials that complain about being priced out of major North American urban centres are hitting a bigger dead end in Hong Kong. The difference is they don’t have a cheaper Whitby, Stoney Creek or Pelham to move to. After a lifetime in Hong Kong, many of the protesters— at a quick glance, mostly in their 20s and 30s —are deeply frustrated and more petrified than ever by increasing Chinese government interference.

“It’s caused a lot of heartache for young people, and families living in subdivided flats,” a Canadian-born billionaire named Allan Zeman told me in his Central Hong Kong office.

This was two years ago, and I was in town mostly to drink, but figured if I was going to fly 14 hours to get there, I may as well get some interviews in.

“It’s caused the polarization in Hong Kong between the haves and the have-nots … this ‘populism’ word, like Donald Trump, has come forward.”

It should be noted that Zeman gave up his Canadian citizenship to become a People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizen in 2008. He was one of the major political backers of Beijing’s hand-picked Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam, the presumably moderate lifelong Hong Konger who has governed the city since 2017, and taken the brunt of the protesters’ criticism of late.

Zeman moved from his native Montreal to Hong Kong in the ‘70s to export clothing. He stayed and ended up developing the area known as Lan Kwai Fong—a playground of bars and nightlife than runs up a steep hill from a major Hong Kong Island thoroughfare—based on, as he told me, Crescent Street in Montreal.

Every night of the week, Zeman’s Lan Kwai Fong is packed with rich locals, expat bankers from Europe and North America, and tourists pounding drinks on the scorching streets. Sometimes seen from that vantage point at afternoon rush hour are dead-eyed others, ascending past the bars on something called the Mid-Levels Escalator, a literal outdoor escalator that climbs the sloped city streets up to the residential areas above.

But in reality, many rank-and-file Hong Kongers—likely most of the people currently protesting — live in high-rise housing estates across the harbour in Kowloon, and in planned towns not far from the Chinese border, like Yuen Long, where some demonstrations recently shifted and highly-suspicious individuals in white t-shirts began beating back the protesters with sticks.

The sort of mass-scale destitute poverty seen elsewhere in Asia was never historically a problem in Hong Kong. While it existed in places, the city was heralded for decades as a flat-tax haven with minimal regulatory hurdles that allowed anyone with enough capital to open a business within a few days. In that era, Hong Kong was the sort of capitalist paradise that some conservatives who claim to be capitalists know nothing about, complete with a public health care system.

Last year, however, Hong Kong’s official poverty rate reached an all-time high of 20 percent. It’s the sort of thing that makes people pine for the good old days, especially when looking at the specter of totalitarian Chinese rule down the road.

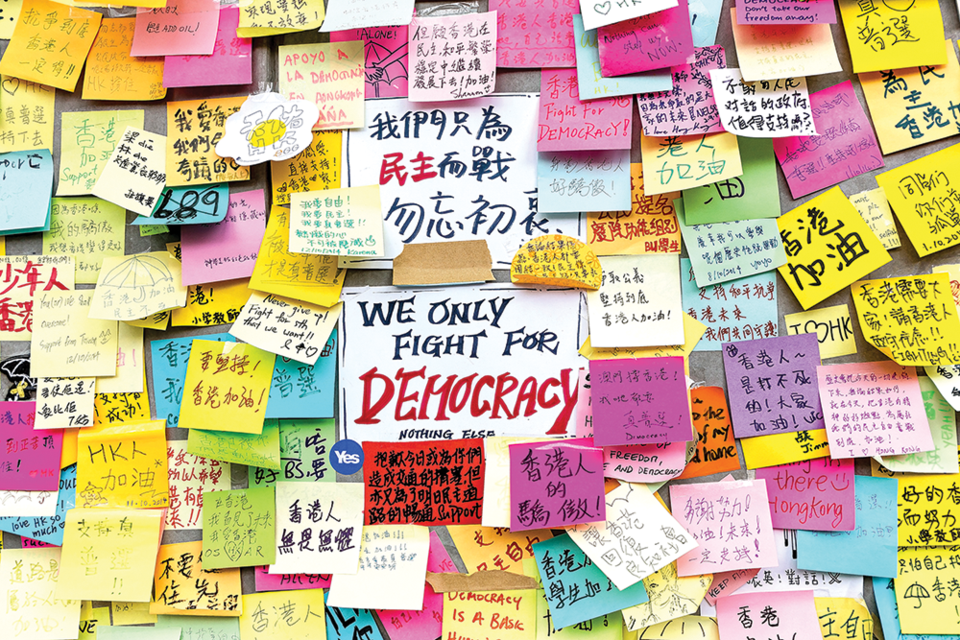

On July 1 — the anniversary of the handover — pro-democracy protesters made their most ballsy move yet, storming Hong Kong’s legislative council chambers in the middle of the night, defacing anything related to China—and, in a scene that might make some modern-day leftists’ heads explode, hung the old British colonial flag on the podium. (Aside from Japanese occupation during the Second World War, Hong Kong was mostly spared the worst aspects of colonialism, such as genocide and residential schools).

“Better to be a foster child in a good home,” my old Hong Kong friend Bernard Wong commented, after I posted the picture on Instagram, “than to be abused by natural parents.”

In truth, Hong Kong should have become an independent city-state, similar to Singapore, in 1997. It had the infrastructure and a century’s worth of democratic know-how to do it. But China saw it as a golden egg, and wouldn’t concede it. Ever since, Beijing’s influence has slowly been chipping away at Hong Kong’s unique identity, even as more and more Western staples like Starbucks pop up all over the city.

It’s difficult to say where it’s all going. The Hong Kong Police— formerly known as the Royal Hong Kong Police under British rule —are becoming more heavy-handed with each protest, and that’s not insignificant. I wouldn’t have called the HKP passive, but I once watched a severely drunken man shout obscenities in five motionless cops’ faces for 15 straight minutes over his unpaid bar bill. At this point, I turned to the Australian next to me and opined that if the guy were in North America, he would have been in a chokehold with his face buried in the pavement. In the end, he was not arrested, and the club’s Nigerian bouncer told me this was probably because “he works in finance.”

The worst fear remains China rolling in tanks and crushing the dissent like they did in Tiananmen Square in 1989. While it’s possible, it’s not likely— yet.

The aforementioned white t-shirt guys have clandestine Beijing operations written all over them, and maybe this and more hard-line police tactics are enough for now. But with the protestors not backing down and some being accused of outright terrorism, the game is getting dangerous. Help or pressure on China isn’t coming from the British or the Americans either, given their own internal distractions with populist politics.

Canadian supporters met in Mount Royal Park in Montreal on Saturday to express their solidarity with the demonstrators, one of many such gatherings reportedly held across the country over the weekend in cities including Halifax, Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary, and Vancouver.

While Hong Kong’s ultimate long-term fate is sealed, as Bloomberg’s Tyler Cowen wrote in June, what’s happening there could be seen as a statement about liberty in the rest of the modern world. ♦